Hence, my mission to research "from whence they came".

I felt if the history of the Arawaks were to be alive and real, I must feel, speak, touch and live with them.

Hence, my mission to research "from whence they came".

My first encounter with Arawak history was my arrival on Anguilla in 1987. My husband had a piece of land directly on the beach in Island Harbour, the fishing capital of Anguilla. We decided to construct an apartment building for short-term tourists. The word was circulated about the proposed construction project. Afterwards we were contacted by Nik Douglas (an archeologist) and Penny Slinger (an artist) where we learned that Arawak artifacts were discovered on the site. The scraping of top-soil in some areas revealed various types of Arawak pottery.

The History of Anguilla revealed that this particular area was an actual site of an Arawak village.

In 1991, our construction project changed from an apartment complex to the Arawak Beach Resort. The Resort depicted six conical style housing with wood shank shingles which represented the thatched roofing on the Arawak housing.

We had a vegetarian restaurant, that served local snapper with Arawak food, i.e. Manioc (corn meal), cassava cakes, vegetarian meats made from corn meal, herbs and spices, vegetables and salads served with homemade sauces from soy and soy products. There were non-alcoholic drinks made from fresh local fruits, papayas, mangoes, passion fruit and limes.

After the sale of Arawak Beach Resort, which is now the Arawak Beach Inn, I still had a passion for the people I never met, it seems as though I was being drawn to them.

I found myself studying more of their history. I thought: "there is nothing here in Anguilla to show the lifestyle and culture of the Arawak Indians". One part of my research led me to the social, religion and political aspects of their culture.

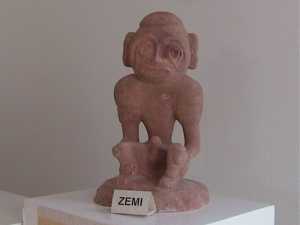

Here I chose to reproduce artifacts that were once a part of a culture that was so real. You can see part of their history in the caverns here in Anguilla with petroglyphs (records of their way of life) inscribed on walls and zemis (different idols of worship), pottery remains which includes fragments of cassava grills, cotton spindles, stone and coral tools. Many of these items are found throughout the Caribbean. I, however. chose to reproduce three that were used on a daily basis by the Arawaks: 1) Zemi, the god of fertility; 2)Bohio (hut), home to several families and 3) the Duho, a ceremonial stool, made of wood or stone with an animal head. This stool was made especially for the Cacique, the Chief, where he resolved all political, religious and domestic disputes.

I had one major problem, finding someone to sculpt the artifacts and then to create a three-dimensional mold for each one. I discovered a young artist on the island,

Diane Samuels (pictured to the right),

who hesitantly took the challenge to do the sculpting.

After several attempts of me telling her "that's not what I'm looking for", she almost gave up. I pleaded with her not to give up, and told her that she was almost there. Finally, we created the three sculptures I had envisioned. Now it was time to construct the molds. Diane told me she did not know how to make the molds for the sculptures. It took me one year to find a mold maker. I was becoming discouraged. One day it was if the Lord said to me call Caribbean Development Bank (CDB), CTCS, Network, the bank I had been dealing with for the past ten years. I phoned and explained what I was doing and asked if they could help me.

Three weeks later, a consultant arrived in Anguilla from St. Lucia. When he entered my office, I became speechless, for I was looking into the face of an Arawak Indian. He introduced himself as

Adam Azaire,

the ceramist. It took me a quarter of the day to fully comprehend who the Lord had sent to me. He is an Arawak who left Guyana to attend a University in England to study ceramics, a natural talent which was inherent from birth. After studying abroad, he went back to Guyana. After living there, he realized that he was not accepted as a ceramist by his people for men did not make pottery. There he moved to Barbados and from there to St. Lucia.

Adam trained Diane in every technique in three-dimensional mold making. The work is very tedious, but the outcome is a work of art.

After meeting Adam, I knew I had to go to Guyana and meet the people my spirit was longing for. Once again, I called CDB for help. I thought that it was highly unlikely that they would arrange a research trip into the jungles of Guyana. But praise God, they accepted my application. A two week research project was arranged for me, comprising one week in Barbados at the Barbados Museum and Historical Society and one week in Guyana where I was attached with a guide Jennifer Wishart of the Amerindian Research Unit of the University of Guyana.

Ms. Wishart told me that I would be unable to enter the interior of the Arawak village because permits were not given to non-indigenous without going through the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). I asked Ms. Wishart if the person was a descendent of another Amerindian tribe would it make a difference, because my father was a descendent of the "Black Creek" tribe in the U.S. Ms. Wishart contacted the Office of the President of the Amerindian Affairs in Guyana to explain that I was from an indigenous origin. That same day Ms. Wishart received a call from the Office of the President of the Amerindian Affairs and was told that she could pick-up a permit to enter into the village of the Arawaks of Kabakaburi.

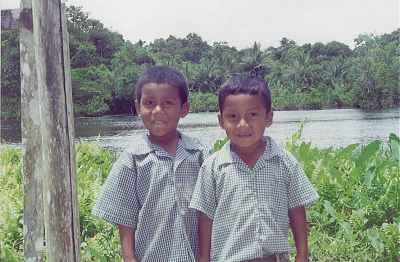

The journey took approximately 3 � hours by taxis and boats.

As we entered the Pomeroon River, I saw numerous canoes with children from ages approximately three to four years and up paddling their way to school. It was exhilarating to see children operate and maneuver the canoes. Walking, canoeing or outboard boating are the only means of transportation.

I was introduced to Mr. Horace and Gloria Lowe, Mrs. Lowe is head mistress of the only school on Kabakaburi. I spent the night with Mr. & Mrs. Lowe where I met Mrs. Lowe's mother Mrs. Ivy Robers. Mrs. Lowe and her mother are two of approximately eight Amerindians who speak the Arawak language fluently. Before entering the village, we had to go through the Captain (Cacique) Mr. Edward Smith. My activities included:

1. Resting in a hand made hammock and listening to tales of the different animals in the forest, which include:

a. the tapir - wild cow

b. wild boar - pig

c. howler monkey - baboon

d. squirrel monkey

e. marmeset monkey

f. jaguar

g. oselot

h. puma

i. pecarri/ local name, lebba - large rodent with no tail, only eat seeds & plants

j. agoti - very fast, a hunter must be very skilled to kill this animal

k. bush deer

2. Eating foods harvested from the grounds, fresh cassava cakes and duff (made from cassava flower) cooked in fresh field peas. (I do not eat meat). A visit with native women at the Kabakaburi Craft Center where I purchased historical artifacts.

3. The Cacique took me down the Pomeroon River (the deepest river in Guyana) and up the Waiwaru Creek to meet his family. There I purchased historical artifacts from his family.

4. A courtesy call was made to Canon John Peter Bennett, Arawak scholar

and author of the Arawak-English Dictionary (with an English word-list)

and the first Arawak priest. Cannon Bennett is in the process of having

the Arawak folklore recorded.

The day was well spent walking through the forest and taking a bath in the creek. The water at first glance seems black and murky, but it is actually filled with the rich minerals of bauxite and particles of gold flowing through.

5. I sat and listened about the way of life in the forest; hunting, farming, building, working. Men still went into the interior to hunt to feed their families, their main foods are the tapir (wild cow), wild boar, agouti and bush deer. Men and women plant ground provisions. Women did pottery and basketry - when enough pottery and basketry was made, women and their children were taken to the Amerindian Residence Craft Shop where they spent days trying to sell their wares. Money is very scarce in the villages.

All houses are close to the river and are elevated on raised stilts or columns. They are constructed in this manner so as to protect families when the river banks overflow.

The kitchen is outside and the half wall and oven are made from lime. The roof is made from leaves of the troolie palm and the roof can last for a minimum of ten years without showing signs of leakage. One family took me into their outdoor kitchen and it seemed as though I had entered into the pages of history. I saw historical pieces that were depicted in history books.

One interesting piece was the turtle shell. I asked the purpose of these, they said the shells were used to burn incense and herbs to ward off evil spirits; every home had one or more turtle shells. I received two that were handed down from their grandparents.

There was so much history in this one kitchen; an old man in his hammock putting his grandchild to sleep; a warishi, a kind of basket with a head strap that is made to carry heavy loads; casareep, a poisonous liquid extracted from cassava that is used as a preservative in their daily cooking. The casareep is used in their pepper pot that preserves cooked meat indefinitely. Theire forefathers' technique of extracting the poison from the cassava is still used today.

All items received from the Arawak and Carib tribes will be displayed in the a museum which will soon be established in Anguilla.

Lack of time did not permit me to explore other areas of the villages and immerse myself deeper into their culture and lifestyle. That is why around October 2002 I plan to return and spend seven nights with the villagers.

I hope those of you who are collectors of historical artifacts enjoy your unusual and unique reproduction of the Arawak Indian artifacts as I have enjoyed researching and reproducing them. As I learn more about this almost extinct culture, I shall share it with you. Thank you again.

Wilma Vanterpool

Anguilla - 2002

The Arawak Indians often had two different type of dwelling houses:

1) The Bohio was the chief's (Cacique) house. In recognition of his status the house should have been rectangular but the Arawaks found this difficult to build and so he was often given a round house which was larger than the family houses.

2) The Caneye was the family house which was round and some rectangular. The usual Arawak house was round and constructed in the following way

a) wooden posts were planted in the ground in a circle and canes were woven between them and tied with creepers.

b) The roof was conical shaped and overlaid with thatch with a hole left in the top through which the smoke could escape.

c) There were no windows and only one opening for a door. The houses were strongly built and sometimes withstood hurricanes.

d) Furniture was sparse, hammocks were used for sleeping purposes.

Pictured right is our reproduction of a Bohio.

Sometimes stools, or even tables were found, but these were very rare. Tools were small and made of stone. Finally there would always be a small statue of a zemi (idol) made of wood, stone or cotton or a basket of bones serving as a zemi.

Outside the houses were the cultivated plots or conucos of the Arawaks. The grounds had plenty of maize, cassava, groundnuts, sweet potatoes, yautia and other crops; some cotton and tobacco were grown in different villages.

This reproduction of the Bohio (hut) was sculptured from clay then caste into a four piece 3-Deministional mold.

The Cacique was more of a ceremonial ruler than a law maker. He dealt with the distribution of land, the ordering of labor on the land and the planting and distribution of crops. He made decisions of peace and war and was the leader in war but he made few laws and the keeping of law and order was a matter for the individual. For example, if someone stole property it was up to the injured party to inflict punishment.

The Cacique was also a religious leader who was greatly respected and given many privileges. His wives could wear longer skirts than other women. His house, which was larger than the other houses, was built for him. His canoe was also built for him by his tribesmen. He was given the best food and he was buried n a marked cave or grave and some of his wives were buried with him.

He had a special ceremonial stool called a Duho which was carved out of wood or stone in the shape of an animal (see model to the right).

As religious leader, the Cacique fixed the day of worship and led the ceremonies playing a wooden gong. He had his own zemis which were felt to be more powerful than any others and thus he commanded additional respect and obedience.

The Arawaks buried their dead and believed in a life-after death in coyaba (heaven), a peaceful place which was free from natural calamities like sickness and hurricanes. There they thought they would meet their ancestors.

Ordinary people could not communicate with gods or ancestors through the zemis so the priests had to pray to cure sickness, or bring good weather, or make the crops grow, or keep away the Caribs (warriors). In religious ceremonies the priests often used tobacco or cahoba (powdered tobacco) which they inhaled directly into their nostrils to induce unconsciousness, the best state for communication with the zemis. If the priest failed to have his prayer answered by the zemis, it was felt that the power of the zemi was to strong. For an important religious ceremony the village would be summoned by blowing a conch shell and the cacique would lead a procession of the whole village. The priests would make themselves vomit by tickling their throats to clear away all impurity before communicating with the zemis.

The Arawaks' religious beliefs were very deep, especially their belief in coyaba, which explains their many suicides rather than enduring life under the cruelty of the Spaniards.

This Zemi reproduction represents the fertility earth-goddess.